VCU is back in session, and while I have the same students (I love this part of my job), I’m amazed that people who seem so familiar can be, with a new subject, totally surprising. Our winter reading is Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, a novel I have taught before, but always in an “Intro to Science Fiction” course. This year I’m teaching it as part of an ethics and critical thinking curriculum, which I’m finding demands a shift to a much more focused interrogation of some of the central questions of the novel—namely how we define ourselves as human. It seems like an easily dismissible question. There are not, for instance, androids among us who pass as human. There are, however, some dramatic ongoing changes in how we define humanity, and in debates about abortion and stem cell research it is by no means a settled issue socially or politically.

On Friday of last week I asked students to write about a passage in the book that highlights just how socially inept the characters are at distinguishing between humans and others. There are tests, of course, throughout the novel, but very few characters ever take the most definitive test of their humanity: a bone marrow sample. Instead, they are left to muddle through social interaction and to use vague categories as their guide.* The scene is Luba Luft’s arrest and retirement. Everyone in this passage has their own deeply invested sense of how we perform our humanity. Luba’s is method to value art, something Phil Resch is wholly unable to do.

Art, the novel seems to argue, demands empathy from its viewer. Art points us toward an ethical framework. It helps us see and give meaningful consideration to the world.

We’re testing this theory in class. For the last ten minutes of every Monday class I’m giving the students a work of art to look at, and I’m staying silent. I’ve asked the students in those ten minutes each week to take over, to regulate their own debate on something with which they are unfamiliar. I’ve asked them if their performance in this capacity can actually prove they’re human.

Their responses are fascinating. Even though I’m bowing out of the conversation, they’re constantly looking to me for support. They’re asking one another questions, panicking when they fall into awkward silence, alternately encouraging and arguing with one another. It’s the start of something new and something that feels productive.

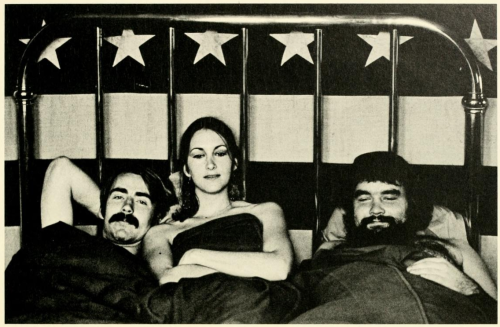

Maman (1999), in Tokyo 2011.

Today I gave them Maman by Louise Bourgeois. The range of their responses was incredible. One class sat in almost complete silence for the full ten minutes, some students occasionally looking up as if to speak and then deciding against it. In other classes some expressed fear and alienation. One student said she wanted to climb it. Several admired the delicate stance of such an enormous object.

Only a couple of students commented that the spider reminded them of the spider in the novel, which Priss and Roy torture. One said quietly that Priss and Roy are right—the spider could certainly walk on four legs.

*imprecise or arbitrary categorizations are some of the most frequent hurdles I run into in the classroom and are some of the hardest habits to overcome.

——

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? New York: Del Rey, 1968.

Malchik, Atom. Roppongi Hills, Mori Tower – Maman (1999), sculpture by Louise Bourgeois. Feb. 2011. Flickr. JPEG file.